Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid, DBE, RA (31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was an Iraqi-born British architect. She was the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 2004. She received the UK's most prestigious architectural award, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, she was made a Dame by Elizabeth II for services to architecture, and in 2015 she became the first woman to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

She was described by the The Guardian of London as the 'Queen of the curve', who "liberated architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity. " Her major works include the aquatic centre for the London 2012 Olympics, Michigan State University's Broad Art Museum in the US, and the Guangzhou Opera House in China. Some of her designs have been presented posthumously, including the statuette for the 2017 Brit Awards , and many of her buildings are still under construction, including the Al Wakrah Stadium in Doha, a venue for the 2022 FIFA World Cup .

Early life and academic career

Hadid's 4th year architecture student project (1976-77) for a hotel on a bridge over the Thames based on a work by the Russian Suprematist artist Kazimir Malevich

Hadid was born on 31 October 1950 in Baghdad, Iraq, to an upper-class Iraqi family. Her father, Muhammad al-Hajj Husayn Hadid, was a wealthy industrialist from Mosul. He co-founded the left-liberal al-Ahali group in 1932, a significant political organisation in the 1930s and 1940s. He was the co-founder of the National Democratic Party in Iraq. Her mother, Wajiha al-Sabunji, was an artist from Mosul. In the 1960s Hadid attended boarding schools in England and Switzerland.

Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving, in 1972, to London to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture. There she studied with Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis and Bernard Tschumi. Her former professor, Koolhaas, described her at graduation as "a planet in her own orbit." Zenghelis described her as the most outstanding pupil he ever taught. ‘We called her the inventor of the 89 degrees. Nothing was ever at 90 degrees. She had spectacular vision. All the buildings were exploding into tiny little pieces." He recalled that she was less interested in details, such as staircases. "The way she drew a staircase you would smash your head against the ceiling, and the space was reducing and reducing, and you would end up in the upper corner of the ceiling. She couldn’t care about tiny details. Her mind was on the broader pictures – when it came to the joinery she knew we could fix that later. She was right.’ Her fourth-year student project was a painting of an hotel in the form of a bridge, inspired by the works of the Russian suprematist artist Kazimir Malevich.

After graduation in 1977 She went to work for her former professors, Koolhaas and Zenghelis, at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Through her association with Koolhaas, she met the architectural engineer Peter Rice, who gave her support and encouragement. Hadid became a naturalised citizen of the United Kingdom. She opened her own architectural firm in 1980

She began her career teaching architecture, first at the Architectural Association, then, over the years, at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge University, the University of Chicago, the Hochschule fur Bildende Kunste in Hamburg, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Columbia University. She earned her early reputation with her lecturing and colorful and radical early designs and projects, which were widely published in architectural journals but remained largely unbuilt. her ambitious but unbuilt projects included a plan for Peak in Hong Kong (1983), and a plan for the Opera in Cardiff, Wales, (1994). The Cardiff experienced was particularly discouraging; her design was chosen as the best by the competition jury, but the Welsh government refused to pay for it, and the commission was given to a different and less ambitious architect. Her reputation in this period rested largely upon her teaching and the imaginative and colorful paintings she made of her proposed buildings. Her international reputation was greatly enhanced in 1988 when she was chosen to show her drawings and paintings as one of six architects chosen to participate in the exhibition "Deconstructivism in Architecture" curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley at New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Early buildings (1991-2005)

Vitra Fire Station (1991-93)

One of her first clients was Rolf Fehlbaum, the president-director general of the German furniture firm Vitra, and later, from 2004 to 2010, a member of the jury for the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. In 1989 Fehlbaum had invited Frank Gehry, then little-known, to build a design museum at the Vitra factory in Weil-am-Rhein. In 1993, he invited Hadid to design a small fire station for the factory. Her designs for the radically fire station, made of raw concrete and glass, was a sculptural work composed of sharp diagonal forms colliding together in the center. Pictures of it appeared in architecture magazines before it was ever constructed. When completed, it never served as a fire station; as the government requirements for industrial firefighting were changed, and it became an exhibit space instead, and is now on display with the works of Gehry and other well-known architects. It became the launching pad of her architectural career.

Bergisel Ski Jump (1999-2002)

She built a complex of public housing in Berlin (1986-1993) and organized an exhibition, "The Great Utopia"(1992), at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Her next major project was a ski jump at Bergisel, in Innsbruck Austria. The old ski jump, built in 1926, had been used in the 1964 and 1976 Winter Olympics. The new structure was to contain not only a ski jump, but also a cafe with 150 seats for a 360 degree view of the mountains. Hadid had to fight against traditionalists and against time; the project had to be completed in one year, before the next international competition. Her design is 48 meters high and rests on a base seven meters by seven meters. She described it as "an organic hybrid", a cross between a bridge and a tower, which by its form gives a sense of movement and speed.

Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati (1997-2000)

At the end of the 1990s, her career began to gather speed, as she won commissions for two museums and a large industrial building. She competed against Rem Koolhaas and other well-known architects for the design of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Ohio (1997-2000). and won, and became the first woman to design an art museum in the United States. It was not an enormous museum (8500 square meters) and her design did not have the flamboyance of the Guggenheim Bilbao of Frank Gehry, built at the same time, but it showed her ability to use architectural forms to create interior drama, including its central element, a thirty-meter long black stairway that passes between massive curving and angular concrete walls.

Phaeno Science Center (200-2005)

In 2000 she won an international competition for the Phaeno Science Center, in Wolfsburg, Germany (2000-2005). The new museums was only a little larger than the Cincinnati Museum, with 9000 square meters of space, but the plan was much more ambitious. It was similar in concept to the buildings of Le Corbusier, raised up seven meters on concrete pylons, but, unlike Corbusier's buildings, she planned for the space under the building to be filled with activity, and each of the ten massive inverted cone-shaped columns that hold up the building contains a cafe, a shop, or a museum entrance. The tilting columns reach up through the building and also support the roof. The museum structure resembles an enormous ship, with sloping walls and asymmetric scatterings of windows, and the interior, with it angular columns and exposed steel roof framework, gives the illusion of being inside a working vessel or laboratory.

Ordrupgaard Museum extension (2001-2005)

In 2001 she began another museum project, an extension of the Ordrupgaard Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, a museum featuring a collection of 19th century French and Danish art in the 19th century mansion of its collector. The new building is 87 meters long and 20 meters wide, and connects by a passage five meters wide with the old museum. There are no right angles, only diagonals, in the concrete shell of the museum. and the floor-to-ceiling glass walls of the gallery made the garden the backdrop of the exhibits.

BMW Administration Building (2001-2005)

In 2002 she won the competition to design a new administrative building for the factory of the auto manufacturer BMW in Leipzig, Germany. The three assembly buildings adjoining it were designed by other architects; her building served as the entrance and what she called the "nerve center" of the complex. As with the Phaeno Science Center, the building is hoisted above street level on leaning concrete pylons. The interior contains a levels and floors which seem to cascade, sheltered by tilting concrete beams and a roof supported by steel beams in the shape of an 'H'. The open interior inside was intended, she wrote, to avoid "the traditional segregation of working groups" and to show the "global transparence of the internal organization" of the enterprise, and wrote that she had given particular attention to the parking lot in front of the building, with the intent, she wrote, of "transforming it into a dynamic spectacle of its own."

In 2004 she was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the most prestigious award in architecture, though she had only completed four buildings, including the VItra Fire Station, the Ski Lift in Insbruck Austria, and the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati. In making the announcement, Thomas Pritzker, the head of the jury, announced: "Although her body of work is relatively small, she has achieved great acclaim and her energy and ideas show even greater promise for the future."

Reputation

Following her death in March 2016, Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times wrote: "...her soaring structures left a mark on skylines and imaginations and in the process reshaped architecture for the modern age...Her buildings elevated uncertainty to an art, conveyed in the odd way of one entered and moved through these buildings and in the questions that her structures raised about how they were supported...Hadid embodied, in its profligacy and promise, the era of so-called starchitects who roamed the planet in pursuit of their own creative genius, offering miracles, occasionally delivering."

Deyan Sudjic of the Guardian described Hadid as "an architect who first imagined, then proved, that space could work in radical new ways...Throughout her career, she was a dedicated teacher, enthused by the energy of the young. She was not keen to be characterised as a woman architect, or an Arab architect. She was simply an architect."

Sometimes called the 'Queen of the curve', Hadid frequently described in the press as the world's top female architect. although her work also attracted criticism. The Metropolitan Museum in New York cited her "unconventional buildings that seem to defy the logic of construction "

Her work also sometimes attracted criticism. Her architectural language was described as "famously extravagant" and she was accused of building "dictator states". Architect Sean Griffiths characterised Hadid's work as "an empty vessel that sucks in whatever ideology might be in proximity to it".

Qatar controversy

As the architect of a stadium to be used for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, in Qatar, Hadid was accused in the New York Review of Books of giving an interview in which she alleged showed no concern for the deaths of migrant workers in Qatar involved in the project. In August 2014, Hadid sued The New York Review of Books for defamation and won. Immediately thereafter, the reviewer and author of the piece in which she was accused of showing no concern issued a retraction in which he said "...work did not begin on the site for the Al Wakrah stadium, until two months after Ms Hadid made those comments; and construction is not scheduled to begin until 2015.... There have been no worker deaths on the Al Wakrah project and Ms Hadid's comments about Qatar that I quoted in the review had nothing to do with the Al Wakrah site or any of her projects. I regret the error.

Style

The architectural style of Hadid is not easily categorized, and she did not describe herself as a follower of any one style or school. Nonetheless, before she had built a single major building, she was categorized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a major figure in architectural Deconstructivism. Her work was also described as an example of parametricism.

When she was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2004, the jury chairman, Lord Rothschild, commented: “At the same time as her theoretical and academic work, as a practicing architect, Zaha Hadid has been unswerving in her commitment to modernism. Always inventive, she’s moved away from existing typology, from high tech, and has shifted the geometry of buildings.

Her work was described in 2016 by Designmuseum as having "the highly expressive, sweeping fluid forms of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry that evoke the chaos and flux of modern life."

Hadid herself, who often used dense architectural jargon, could also describe the essence of her style very simply: "The idea is not to have any 90 degree angles. In the beginning, there was the diagonal. The diagonal comes from the idea of the explosion which "re-forms" the space. This was an important discovery."

Awards and Honors

Hadid was named an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and an honorary fellow of the American Institute of Architects. She was on the board of trustees of The Architecture Foundation.

In 2002, Hadid won the international design competition to design Singapore's one-north master plan. In 2004, Hadid became the first female and first Iraqi recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. In 2005, her design won the competition for the new city casino of Basel, Switzerland and she was elected as a Royal Academician. In 2006, she was honoured with a retrospective spanning her entire work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York; that year she also received an Honorary Degree from the American University of Beirut.

In 2008, she ranked 69th on the Forbes list of "The World's 100 Most Powerful Women". In 2010, she was named by Time as an influential thinker in the 2010 TIME 100 issue.

In September 2010, New Statesman listed Zaha Hadid at number 42 in their annual survey of "The World's 50 Most Influential Figures 2010". Hadid was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2002 and Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2012 Birthday Honours for services to architecture.

She was listed as one of the "50 Best-Dressed over 50" by the Guardian in March 2013. Three years later, she was assessed as one of the 100 most powerful women in the UK by Woman's Hour on BBC Radio 4.

She won the Stirling Prize two years running: in 2010, for one of her most celebrated works, the MAXXI in Rome,[79] and in 2011 for the Evelyn Grace Academy, a Z‑shaped school in Brixton, London.[80] She also designed the Dongdaemun Design Plaza & Park in Seoul, South Korea, which was the centrepiece of the festivities for the city's designation as World Design Capital 2010. In 2014, the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, designed by her, won the Design Museum Design of the Year Award, making her the first woman to win the top prize in that competition.[2]

In January 2015, she was nominated for the Services to Science and Engineering award at the British Muslim Awards.[81]

In 2016 in Antwerp, Belgium a square was named after her, Zaha Hadidplein, in front of the extension of the Antwerp Harbour House designed by Zaha Hadid.

1982: Gold Medal Architectural Design, British Architecture for 59 Eaton Place, London

1994: Erich Schelling Architecture Award[82]

2001: Equerre d'argent Prize, special mention[83]

2002: Austrian State Prize for Architecture for Bergiselschanze

2003: European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture for the Strasbourg tramway terminus and car park in Hoenheim, France

2003: Commander of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for services to architecture

2004: Pritzker Prize

2005: Austrian Decoration for Science and Art[84]

2005: German Architecture Prize for the central building of the BMW plant in Leipzig

2005: Designer of the Year Award for Design Miami

2005: RIBA European Award for BMW Central Building[85]

2006: RIBA European Award for Phaeno Science Centre[86]

2007: Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture

2008: RIBA European Award for Nordpark Cable Railway[86]

2009: Praemium Imperiale

2010: RIBA European Award for MAXXI[87]

2012: Jane Drew Prize for her "outstanding contribution to the status of women in architecture"[88]

2012: Jury member for the awarding of the Pritzker Prize to Wang Shu in Los Angeles.

2013: 41st Winner of the Veuve Clicquot UK Business Woman Award[89]

2013: Elected international member, American Philosophical Society[90]

She was also on the editorial board of the Encyclopædia Britannica.[91]

Antwerp Port Office

Zaragoza Bridge

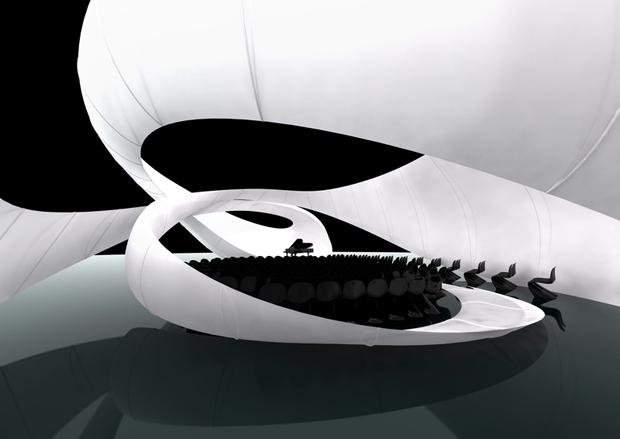

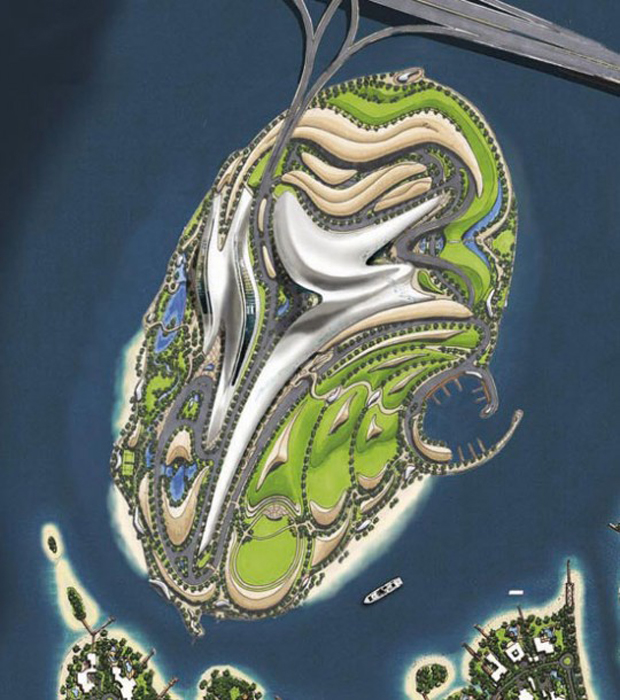

Dubai Operahouse